So you want to be a special operator? Great. You can handle stressful situations. Check. You have a strong mindset. Check. But none of those things will matter if your body breaks.

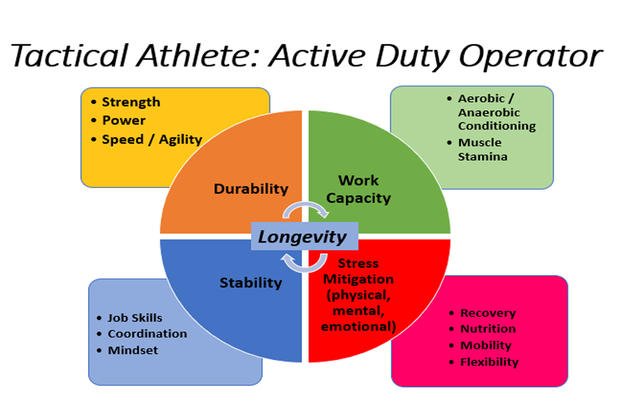

Durability, work capacity, stability and stress mitigation are the products of years of hard work, training and learning how your mind and body perform under stress.

The below graphic describes the elements of fitness important to the tactical athlete.

Having a durable and more resilient body to handle the daily stresses of running many miles, rucking heavy weight, and moving logs and boats for hours is something that can come only with work. This type of durability often is gained through years of persistent and consistent training through sports, martial arts, even manual labor.

If you still are growing, you can enhance your strength, endurance, speed and other elements of fitness, but your true durability is not quite developed yet. This is why many college sports programs will offer redshirt years (a fifth year of athletic eligibility) to their younger players, so they can grow, mature, improve their skills and start to build a foundation of strength that will help to create durable bones, joints and muscles. It takes time to grow into a durable body.

When the human body has finished growing, the ability to adapt to stress (running/lifting/load bearing) will come in the form of stronger bones. The journey may include aches, pains, shin splints and stress fractures, but these are typically from doing too much, too soon and not progressing over time. Durability comes with time under a variety of stress. Patience in training is key to developing the type of durability you need.

Durability is the ability to withstand wear, pressure, damage and other stresses. Resiliency, or mental toughness, is similar but typically focuses on mental strength and how the mind handles stress. The mind often will fail long before the body. That is the challenge: Balancing the strong, durable body with the strong, resilient mind.

Describing durability can be vague unless some objective grading parameters can be discussed. How do you build durability?

1. Strength training. Making calisthenics harder with weight vests or TRX and progressing into lifting weights are logical steps to building bone, muscle and joint strength with a wide range of usefulness in a day’s work. Squats, deadlifts, hang cleans and push presses will help with the type of strength and durability the body needs under a log or boat.

2. Working out and working combo. Preparing for a long day of special-ops selection training is difficult to mimic in a weight room or long-distance cardio workout. After a long, challenging workout consisting of a calisthenics warmup, weight training and some form of moderately paced cardio (run, swim, ruck), a candidate needs to keep moving throughout the day. This can be at work, school or, even better, doing some form of manual labor. Topping off the day with a second workout some days will help you build the type of durability (and work capacity) needed for success. As the saying goes, “There is no 30-minute gym workout that will prepare you for a day of spec-ops training. You have to put in your time.”

3. Running progression. The impact forces of running alone will challenge the most durable of legs. Add boots, rough terrain (sand, hills, pavement), and a steep time and distance curve. Your running progression needs to be logical. If you are running 10 miles a week now, increase the time or distance running each week no more than 10%-15% a week.

But make sure you are not just doing long, slow distance running. Your running should have a purpose. It should be to meet the minimum standard with ease. For many selection programs, if you can run between a six- and seven-minute mile pace, you are solid. If you can do 4-5 miles in 28-35 minutes, you will be good to go. Any faster is more cushion.

So run with a purpose of pace, but just slow distance. For most people, the running forces break them.

4. Load-bearing progression. Learning how to change your run style so you can do it with a ruck (backpack) of 40-50 pounds and fast is critical. See the “What is a Ruck?” article. Learn your pace, but first, that foundation of strength needs to play a part. Adding the lower-body strength lifts like squats, lunges, deadlifts, farmer walks, sandbag runs and movements of weight up hills and stairs will help you build the type of leg and lower-back durability that will enable you to handle time under stress. Whether it is a log, boat, a person or other pieces of equipment, learning how to move gear from A to B in a variety of ways will help you build the ability to withstand the stressful forces of gravity and added weight.

Related article:

How to Train to Be a Tactical Athlete

Work Capacity – What is Yours?

Stew Smith is a former Navy SEAL and fitness author certified as a Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) with the National Strength and Conditioning Association. Visit his Fitness eBook store if you’re looking to start a workout program to create a healthy lifestyle. Send your fitness questions to stew@stewsmith.com.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for fitness and basic training tips, or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.