Editor's Note: In this second installment of a two-part series on leadership and readiness, the article argues that the future of military advantage lies not in weapons or algorithms, but in character science—the emerging field that examines how integrity, judgment, and moral courage can be measured, developed, and embedded within military culture.

Every generation of military leaders looks for the next big edge. For my generation, it was technology — smarter systems, better sensors, and data on everything that moves. For today’s leaders, it’s artificial intelligence, machine learning, and autonomous systems.

But the truth is this: the next major leap in military readiness won’t be digital. It’ll be moral.

It’s what some researchers and educators are calling character science, the study of how virtues like integrity, humility, and moral courage develop, how they shape human judgment, and how they directly impact performance when things go sideways. In short, it’s the science behind what we used to call leadership by example.

Character as Combat Power

The U.S. military is unmatched in technology and training. But as every commander knows, tools alone don’t win wars…people do. And people don’t fight, follow, or endure hardship for policies or paychecks. They do it for trust.

Research backs that up. The Center for the Army Profession and Leadership (CAPL) found that “character competency”, not just technical ability, is the strongest predictor of trust across hierarchical boundaries. Units with leaders perceived as morally grounded report significantly higher cohesion and performance under stress.

That’s not surprising to anyone who’s led troops in difficult conditions. When the mission turns ambiguous, or the guidance from higher gets fuzzy, people don’t look to a manual. They look to the leader. And what they’re really asking is simple: Can I trust you to do the right thing when no one’s watching?

The Neuroscience of Doing Right

For years, moral behavior was treated as something we “just know.” But neuroscience has shown it’s far more complex —and, interestingly, trainable.

Studies by neuroscientist Jorge Moll have mapped how moral reasoning activates both the prefrontal cortex (logic) and limbic system (emotion). In other words, ethics isn’t just intellectual; it is embodied. Leaders who regularly reflect on moral choices actually strengthen the neural pathways that help them stay calm and clear under ethical pressure.

That has real operational consequences. Leaders who can regulate emotion, think critically, and align values with mission intent make faster, better, and more consistent decisions. In high-tempo environments, that’s not “soft skill”, it is a survival skill.

Leadership is a potent combination of strategy and character. But if you must be without one, be without the strategy (Norman Schwarzkopf)

From Compliance to Character

For too long, much of our leadership training has focused on compliance: checklists, rules, and processes designed to prevent failure. Important? Absolutely. But compliance doesn’t create courage.

True leadership comes from reflection and formation, developing judgment and conscience before the crisis hits. That’s where character science comes in. It helps leaders understand how values become habits, and how those habits become culture.

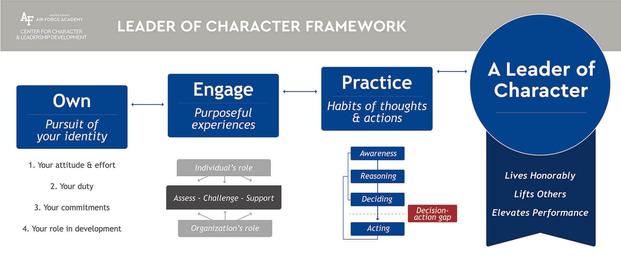

Across the services, encouraging signs are emerging. For example, the United States Air Force Academy, through the Center for Character & Leadership Development, developed the Leader of Character Framework and a strategy for training and educating toward it. This creates an environment where cadets can own, engage, and practice the habits of honorable thoughts and actions in line with a leader of character. They define a leader of character as someone who:

- Lives honorably by consistently practicing the virtues embodied in the core values (Integrity First, Service Before Self, and Excellence in All We Do);

- Lifts others to their best possible selves; and,

- Elevates performance toward a common and noble purpose.

In plain English, when you make character development deliberate, people get better at it.

Measuring What Matters

The military is great at measuring physical fitness, marksmanship, and technical qualifications. But we still struggle to measure moral fitness. That’s changing.

Emerging character assessment tools give leaders data on how cadets and officers are developing ethically, not just operationally. These metrics don’t replace human judgment; they inform it.

Imagine a future where every leadership evaluation includes validated indicators of trustworthiness, empathy, and integrity, not as afterthoughts, but as core readiness components. That’s not science fiction. It’s already happening in early programs across the services.

The National Security Case for Character

So why does this matter for national defense? Because the future battlefield will test not just what we can do, but what we should do.

Artificial intelligence, autonomous weapons, and cyber operations all introduce moral ambiguity that no algorithm can solve. When a strike decision involves both tactical data and ethical consequences, we’ll rely on leaders whose character is as developed as their competence.

Gen. Charles Q. Brown said it plainly last year:

“Trust, accountability, and moral judgment are the strategic advantages our adversaries cannot replicate.”

Our technology can eventually be copied. Our character cannot, unless we neglect it.

Operationalizing Character

If the Department of War wants to get serious about character science, it should move on three fronts:

- Institutional Will. Treat character as a measurable, mission-critical competency, not a “nice-to-have.” Embed it leader development doctrine, and determine how it can be integrated into readiness reports.

- Programmatic Integration. Incorporate virtue-based reflection and ethical decision scenarios into every training pipeline, from boot camp to professional military education.

- Cultural Reinforcement. Determine how to integrate moral courage into command selections and promotion considerations as visibly as those who demonstrate tactical success. When courage pays, culture changes.

This isn’t about moral preaching. It’s about building resilient leaders who can operate under uncertainty and still do the right thing, something the military has attempted to do since its inception.

The Real Frontier

Everyone’s chasing AI, quantum computing, and hypersonics. Rightly so. But the next true advantage will come from leaders who can pair all that innovation with wisdom, empathy, and restraint.

Character science doesn’t replace technology. It ensures the people wielding it are ready, ethically, emotionally, and mentally, for what comes next.

Technology may extend our reach.

Character will define our restraint.

And in the wars of tomorrow, that balance will decide who truly wins.