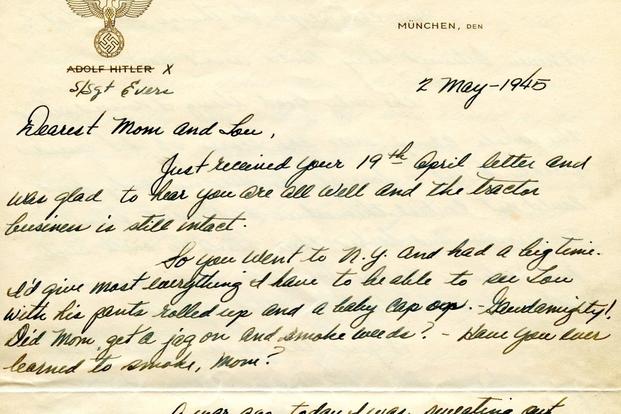

All of the U.S. graves were fresh across Europe for Memorial Day in May 1945, when a battle-weary GI in Munich a few weeks earlier grabbed some of the Fuhrer's stationery to write a letter home.

Army Staff Sgt. Horace Evers crossed out Adolf Hitler's name, scribbled in his own, and wrote about what he had done in the war, and what it had done to him.

"Dearest Mom and Lou (his stepfather)," began the correspondence. He asked about the tractor business back home, and he wished he had been with them on their daring trip to wicked New York City.

Then the words spilled out on how beyond strange his soldier's life had become. He had fought, he had killed, he had witnessed the unspeakable in the death camps. He had survived when so many hadn't, and now he was sitting in Adolf Hitler's living quarters in Munich.

"A year ago I was sweating out shells on Anzio beachhead. Today I am sitting in Hitler's luxuriously furnished apartment in Munich writing a few lines home -- what a contrast," Evers wrote. "A still greater contrast is that between his quarters here and the living hell of Dachau concentration camp only 10 miles from here."

"How can people do things like that? I never believed they could until now," Evers said. "I've shot at Germans with intent to kill before but only because I had to or else it was me. Now I hold no hesitancy whatsoever."

A few more days of the war in Europe were left for Evers and the other GIs who had defeated the Wehrmacht. He wrote the letter on May 2. Five days later in Reims, France, Gen. Alfred Gustav Jodl signed Germany's unconditional surrender to the allies. Jodl would be hanged in 1946 for war crimes.

Boyd Lewis of United Press was among the correspondents who had been summoned to a plane in Paris on 15 minutes' notice for the flight to Reims. They were told only that they would be on "an important out-of-town assignment."

Aboard the Douglas C-47, Brig. Gen. Frank Allen Jr., of Cleveland, director of press operations at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) told the reporters that they would be covering "the biggest story in a war correspondent's life -- the peace story," Lewis wrote.

Allen added "This will be your first uncensored story -- when the surrender is completed, censorship goes off." The reporters "enjoyed a good laugh" at that, Lewis wrote.

In his dispatch, Lewis did something the big picture historians rarely do. He listed some of the everyday soldiers, like Evers in Munich, who were taking part in a momentous event.

He noted the military police who guarded the German entourage at a guesthouse and, of course, their hometowns. "They were Pfcs. Jack Arnold of Lancaster, Pa.; Charles Trautner of Oakland, Calif.; Joseph Fink of Detroit; Frederick Stone of Pittsburgh; Clifford Cleland of Plattsburg, N.Y., and Elmer L. Cole of Little Falls, N.J. WAC (Women's Army Corps) Pfc. Joyce Bennett, of New York City, was manager of the house."

On May 8, Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel signed similar surrender documents in Berlin. He also was executed in 1946 for war crimes.

It was Victory in Europe, what would become just "VE Day," but the celebrations for the troops were mixed with anxiety, said Andrew Carroll, founding director of the Center for American War Letters at Chapman University in California, where Evers' letter on Hitler's stationery is preserved.

In 2017, Carroll began a "Million Letters Campaign" to find and preserve at least 1 million articles of correspondence from every U.S. conflict, "from hand-written missives penned during the American Revolution to e-mails sent from Iraq and Afghanistan."

In donating his letter to the archive after the war, Evers, who was living in Florida, told Carroll that "I'm afraid if I leave the letter (after his death), somebody is going to throw it out."

Evers and the other troops in May 1945, leading up to a somber Memorial Day on May 28, also knew that they might be shipped off to another bitter fight in the Pacific. They knew that the Marines were then engaged in hellish combat on Okinawa. They knew that Gen. Douglas MacArthur was gearing up for the invasion of Japan.

On May 8, "the front-line troops didn't celebrate VE Day the way they did at home," Carroll said. "There was a solemnity and a soberness about what had been lost. And these guys were bracing for the fact that they might have to fight again in the Japanese islands."

Across Europe, where U.S. troops were stationed on May 28, they turned out before the endless rows of white crosses in the cemeteries.

At the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery in Nettuno, Italy, Army Lt. Gen. Lucian Truscott, Jr., who had led the U.S. Sixth Corps through heavy fighting in Italy, presided at the Memorial Day event.

There was no transcript of Truscott's speech, but Stars & Stripes reported he said, "All over the world, our soldiers sleep beneath the crosses. It is a challenge to us -- all allied nations -- to ensure that they do not and have not died in vain."

What happened next was reported by Bill Mauldin -- the Pulitzer Prize winner for his "Willie and Joe" cartoons in Stars & Stripes -- in his 1971 memoir "The Brass Ring," Nicolaus Mills, an American Studies professor at Sarah Lawrence College, told CNN.

"Before the stand were spectator benches, with a number of camp chairs down front for VIPs, including several members of the Senate Armed Services Committee," said Mauldin, who was at the ceremony.

Truscott turned his back on the audience and spoke directly to the white crosses. He "addressed himself to the corpses he had commanded here. It was the most moving gesture I ever saw. It came from a hard-boiled old man who was incapable of planned dramatics," Mauldin said.

"He apologized to the dead men for their presence here. He said everybody tells leaders it is not their fault that men get killed in war, but that every leader knows in his heart this is not altogether true."

"He said he hoped anybody here through any mistake of his would forgive him, but he realized that was asking a hell of a lot under the circumstances. He promised that if in the future he ran into anybody, especially old men, who thought death in battle was glorious, he would straighten them out. He said he thought that was the least he could do."

As Truscott spoke in Italy, the town's burghers in top hats came to the cemetery at Margraten in the Netherlands to honor those from the U.S. 30th Infantry Division who had liberated them. In grainy and silent footage of the event, little girls in traditional dress skipped past stone-faced American MPs to join their parents at the gravesites.

Some of the Dutch carried wreaths for the fallen GIs. A nun and two girls knelt and prayed. Grim U.S. officers paused to salute before the crosses and Stars of David.

In his letter home, Horace Evers went on at length about his bitterness over the death camps, but he also wrote of his satisfaction at having taken part in the liberation.

"I guess the papers have told you about the 7th Army taking Nurnberg and Munich by now," he wrote to his mother and stepfather. "Our division took the greater part of each place and captured many thousands of prisoners."

"We also liberated Russian, Polish and British and American prisoners by the thousands -- what a happy day for those people." He closed with "Well, enough for now, miss you all very much, your son, Horace."