A tragic cost of war is that many service members are missing limbs when they come home from combat. The U.S. military is working harder than ever to replace them with prosthetics that work just like the real thing.

The high-tech whizzes at DARPA, the military research arm of the Defense Department, displayed some breakthrough technology for space, ocean, robotics and ground war at a Congressional Tech Showcase in Washington earlier this month.

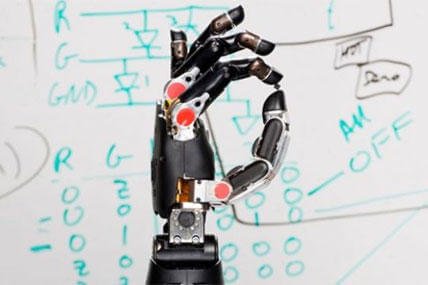

But the most inspiring tech was an innovation underway for America's veterans who return home with upper limb loss. The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab Modular Prosthetic artificial limb, part of DARPA's Revolutionizing Prosthetics Program, is among the most sophisticated arms ever made.

The artificial limb moves like the real thing, and it can do just about everything. Built over the course of five years, it makes it possible to play the piano, toss a ball, pick up a cup and sip some coffee from it.

The ultimate goal is to give back natural hand movement.

The prosthetic weighs about as much as a human arm and looks pretty close to the real thing -- except this arm is made of metal.

And just like a human arm, it's directed by the brain.

How does it work?

Prosthetics currently in use can be disappointing to their wearers. Existing motorized arms offer some range of motion, but they can be hard to control, and sometimes they malfunction.

In 2006, DARPA launched the Revolutionizing Prosthetics program to accelerate advances in arms with two state-of-the-art programs: the Gen-3 Arm System and the Modular Prosthetic Limb.

The goal is to give users much greater control over the hand and arm than currently available devices provide. Thanks to sensors that send signals to the brain, wearers will be able to activate individual fingers, work through a full range of motion and feel whatever they grasp or move.

Simple movements like opening a hand or picking up a baseball involve complex work in the brain. The DARPA / Johns Hopkins approach takes the complicated work behind these movements and reduces it to simple thoughts.

Approaches to control artificial limbs can vary. Some patients use a surgical process called re-innervation that uses sensors implanted in their shoulders, pectoral muscles and residual limbs to direct their arms. Others use non-surgical methods, and they can still pick up something the size of a button.

To achieve the goal of a "natural" arm and hand, this hand has five dexterous fingers that will be capable of many tasks. It will also have a bendable and twistable wrist, an elbow that can both bend and lift weight, and a flexible shoulder that can reach behind the back.

Ultimately, its designers hope it will have a "skin" covering that looks like skin -- it will even wrinkle -- and will be weather- and tear-resistant. And it will "feel."

The other big challenge is to harness the patient's central nervous system to control the arm -- and this work is proving that it's possible to give patients back the sense of touch.

Beyond DARPA, other programs are making strides.

For example, the Alfred E. Mann Foundation announced this week that a U.S. Marine, Staff Sgt. James Sides, received a prosthetic arm with an implantable myoelectric sensor system.

Other programs are also underway in Europe; researchers in Sweden have looked into a bone-anchored mechanical arm with implanted neuromuscular electrodes.

All of these advancements offer hope to those who need it most.

Ballet dancer turned defense specialist Allison Barrie has traveled around the world covering the military, terrorism, weapons advancements and life on the front line. You can reach her at wargames@foxnews.com or follow her on Twitter @Allison_Barrie