Historical fiction plays up places like Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, England, as romantic and exciting despite the very real threat of Nazi invasion and bombing during World War II. Women made up about 75% of the workforce at Bletchley Park, which consisted of jobs operating cryptographic and communications machinery and translating documents. Some even were breaking code with the legendary Dilly Knox, who helped decrypt the Zimmermann telegram that brought the U.S. into World War I and broke the German Naval and Abwehr Enigma codes during World War II.

But on the other side of the ocean from these Bletchley Park women -- many of whom were military spouses who worked together to find out the status of their husbands’ ships and units -- one very smart American military spouse was working to break codes as well.

When Elizebeth Smith graduated with a degree in English literature in 1915, the world was already at war. A year later, she began working at Riverbank Laboratories in Illinois, one of the first places in the U.S. founded to study cryptography. Riverbank was founded by George Fabyan, and the initial staff of 15 people included William Friedman, whom Smith married in May 1917.

Friedman, who trained Army officers at Riverbank, then enlisted in the U.S. Army and served as personal cryptographer for Gen. John J. Pershing.

The Friedmans worked together in Illinois until 1921, when they moved to Washington, D.C., to work as a team for the War Department. William Friedman became the chief cryptanalyst, and Elizebeth deciphered messages through the Prohibition years and broke codes written in Mandarin. Elizebeth and William worked together frequently, but she made several cryptological contributions on her own.

Elizebeth moved to work for the Navy, the Treasury Department and, eventually, the Coast Guard. She solved most intercepts herself and also spent time teaching others how to decrypt coded messages. She relocated to Houston to solve smuggling traffic cases and decrypted 24 coding systems used by the smugglers. In three years, she solved more than 12,000 messages in three years. She also helped indict Al Capone.

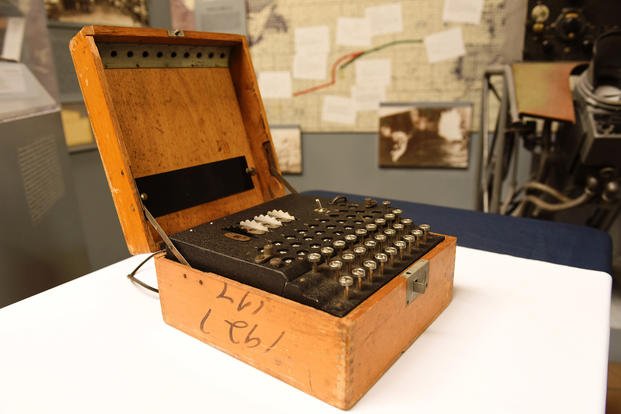

During World War II, Elizebeth worked for the Navy and focused on Operation Bolivar, the German network in South America. Her team was the primary codebreakers for the South American threat, and they broke three Enigma machines. Her team decoded 4,000 messages from 48 radio circuits during the war.

After the war, she consulted with the International Monetary Fund. Friedman, who was 88 years old when she died in 1980, was inducted posthumously to the National Security Agency Hall of Fame in 1999 -- the year of its creation. During the NSA's 50th anniversary in 2002, the OPS1 building was dedicated as the William and Elizebeth Friedman Building. A Coast Guard Cutter was named after her, and a television documentary series called "American Experience" has an episode based on her.

The Mob Museum in Las Vegas includes Elizebeth Smith Friedman among its list of notable names, mostly in reference to the work she did during the Prohibition Era.

--Rebecca Alwine can be reached at rebecca.alwine@monster.com. Follow her on Twitter @rebecca_alwine.

Keep Up with the Ins and Outs of Military Life

For the latest military news and tips on military family benefits and more, subscribe to Military.com and have the information you need delivered directly to your inbox.