Between June 15 and July 29, 1945, six Army Air Forces pilots flying experimental Sikorsky helicopters evacuated between 75 and 94 wounded American soldiers from the Philippine jungles while under Japanese fire. Their mission was to transport aircraft parts, not casualties, but the pilots felt differently.

Those six weeks of improvised rescues became the first combat helicopter medical evacuations under hostile fire in military history. While the numbers were small compared to later conflicts, it proved that helicopters could save lives on the battlefield - a concept that would reshape military aviation and lead directly to Army MEDEVAC and Air Force Pararescue units today.

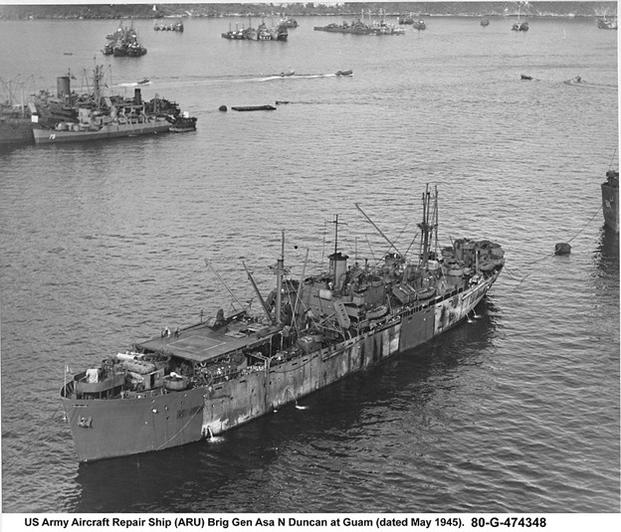

A Floating Repair Solution

As American forces island-hopped across the Pacific in late 1943, damaged aircraft were piling up at forward airstrips without adequate repair facilities. European bases had established infrastructure with machine shops and trained mechanics. Pacific airfields usually didn't.

Gen. Henry "Hap" Arnold, commanding the Army Air Forces, authorized a classified program to convert six Liberty ships into floating maintenance depots, each carrying 344 personnel. Eighteen smaller auxiliary vessels with 48-person crews would handle fighter aircraft maintenance. The ships would be stocked with machine shops, specialized tools, and massive inventories of replacement parts for B-29 bombers and P-51 Mustangs.

According to Lt. Col. Matthew Thompson, who led the training effort, the program got its code name when someone suggested "Ivory Soap" during a planning meeting - both the soap and the repair ships would float.

Thompson had to train 5,000 airmen to become sailors in less than five months. Ed Roberts, owner of the Grand Hotel in Point Clear, Alabama, donated his resort to the military. Training began July 10, 1944. The hotel became a maritime school where trainees called floors "decks," kept time by a ship's bell, and followed Navy protocols for smoking.

By October 1944, the first converted Liberty ship departed Mobile. All six reached the Pacific by February 1945, supporting operations at Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and the Philippines. Unlike most other ships of the time, each repair ship featured a 40-by-72-foot steel platform for helicopter operations.

Helicopters Join the Fleet

The Sikorsky R-4 helicopters assigned to the ships were experimental. Under ideal conditions, the aircraft could carry only 195 pounds beyond pilot and fuel - enough for small components like propeller hubs but not much else. A 1943 Navy report had already concluded the R-4 wasn't suitable for shipboard operations.

Their mission was straightforward: ferry parts and mechanics between ship and shore. Nobody planned on using them for much else.

On June 15, 1945, the 38th Infantry Division requested the evacuation of two soldiers with head injuries from a location 35 miles east of Manila. Second Lt. Louis Carle launched from the Fifth Aircraft Repair Unit in Manila Bay.

After nearly flying into an American P-47 bombing run, Carle reached the designated position and landed. The infantry soldiers stared in disbelief - none had ever seen a helicopter before. The wounded officer needed immediate transport, but the R-4 had no stretcher mounts or medical equipment.

The soldiers improvised. They removed one seat, laid the injured lieutenant on the floor, and propped his feet against the rudder pedals. The arrangement eliminated Carle's tail rotor control, but he delivered the patient to a field hospital near Manila.

Word of the innovative rescue spread quickly, and requests for helicopter evacuations increased. On June 17, 1st Lt. Robert Cowgill returned with a newly assembled R-6A, a slightly improved but more cramped variant. While Carle flew patients who couldn't stand, Cowgill transported those who were slightly wounded. Carle once flew seven hours in one day, completing six evacuation missions, a remarkable accomplishment for the time.

The helicopters were difficult to fly. Wooden and fabric blades vibrated excessively and required constant adjustment. The control stick circled continuously, never staying still. Pilots manually coordinated the throttle with collective pitch since there was no regulated rotor speed. A June 21, 1945,The Chicago Tribune report noted the control stick vibrated like a jackhammer, requiring a constant firm grip or the aircraft would fall out of the sky.

Philippine heat, humidity, and elevation reduced the R-4's lifting capacity to nearly zero. Carle developed a dangerous technique: he intentionally over-revved the engines and rotors past maximum rated speeds to generate enough lift for takeoff with a passenger. The method risked blade failure and engine damage, but it worked. In a 1947 American Helicopter magazine article, Carle wrote that shortening engine life was preferable to shortening human life.

On June 21, both Carle and Cowgill crashed when their rotors hit trees during landing attempts in a tight jungle clearing. Carle ended up with wood fragments lodged in his skull. He ordered some troops to destroy his wrecked helicopter with bazooka rounds, then hiked out to American lines. Cowgill walked out of the mountains over four days, encountering Japanese forces along the way. The Fifth Aircraft Repair Unit departed for Okinawa, ending that ship's rescue operations.

Days later, the Sixth Aircraft Repair Unit arrived in Manila Bay. Three pilots - 1st Lt. James Brown, 2nd Lt. John Noll, and Flight Officer Edward Ciccolella - flew approximately 40 evacuation missions over four days. Ship mechanics even welded rescue baskets to the steel frames as external litters, allowing transport of prone patients without cramming them inside the cabin.

Their operations continued through July. Historical records show the pilots evacuated between 75 and 94 wounded personnel, with some uncertainty in the exact count.

Lt. Carter Harman of the First Air Commando Group had flown the first helicopter medical evacuation in Burma on April 23, 1944, but the Ivory Soap pilots were the first helicopter crews targeted by enemy ground troops.

From WWII Innovation to Today's MEDEVAC

The numbers of helicopter evacuations from Operation Ivory Soap were small - fewer than 100 missions. Korea saw approximately 20,000 helicopter medical evacuations. Vietnam reached almost one million. But the 1945 missions in the Philippines established the fundamental concept that helicopters could reach wounded soldiers faster than any other method, and that speed saved lives.

The missions proved that helicopters could operate in terrain inaccessible to ground vehicles and aircraft. They demonstrated that even primitive rotorcraft with severe limitations could function as battlefield ambulances when properly adapted. Ship mechanics, welding external litters, and pilots removing seats to fit casualties became the foundation for purpose-built medical evacuation helicopters in later wars.

Today's Army MEDEVAC crews flying UH-60 Black Hawks and Air Force Pararescue teams operating HH-60 Pave Hawks trace their lineage directly to those six pilots in 1945. Modern military helicopters carry specialized medical equipment, trained medics, and can evacuate multiple casualties simultaneously - capabilities the Ivory Soap pilots couldn't imagine.

According to Department of Defense statistics, rapid helicopter evacuation has contributed to the lowest combat mortality rates in American military history.

The Grand Hotel in Point Clear still operates as a resort. During the property's 150th anniversary in 1997, staff renamed room 1108 - Thompson's wartime command post - the Thompson Suite. The hotel conducts a daily 3:45 p.m. ceremony with a procession and cannon firing to commemorate the mission. Thompson died in 2005 at age 99.

An exhibit at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, honors Operation Ivory Soap. A memorial plaque was dedicated there by the Floating Aircraft Repair and Maintenance Association on Oct. 3, 1997.