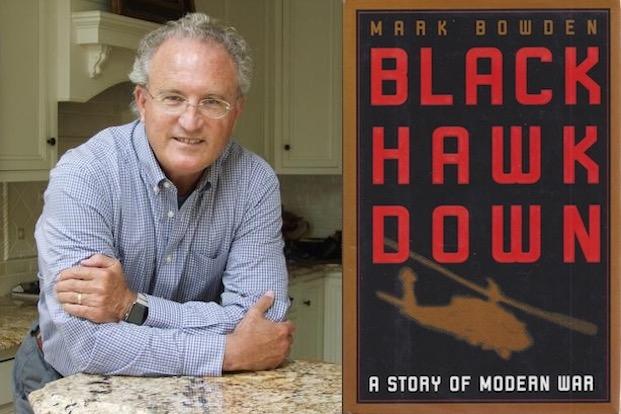

Journalist and author Mark Bowden had already enjoyed a successful career when his investigation into the Battle of Mogadishu and subsequent book "Black Hawk Down" launched him into his current role as one of America's most respected history writers.

The movie version of "Black Hawk Down" has just been upgraded and reissued in a spectacular new 4K UHD version supervised by director Ridley Scott.

Since the story of the movie tracks back to Mark Bowden's original series of investigative stories in the Philadelphia Inquirer and his 1999 book, he spoke with us about his own experiences and offered valuable background on the real-life history for anyone too young to remember the actual events of 1993.

Bowden has written more than a dozen books in his celebrated career, but we also checked in with him on the status of his 2017 Vietnam War history, "Hue 1968," and talked about his new true crime history, "The Last Stone."

A lot of our readers are too young to remember the events in Somalia. What kind of shock was it in 1993 when it happened? Did Americans have an idea of what the military was up to in the world? Is it something that people were paying attention to in the lead-up to when it happened?

I don't think people had been paying close attention to what was going on in Somalia. It had created a lot of news when Marines first landed there in December of 1992. In fact, there were CNN cameramen on the beach. So, there was a lot of attention focused on the humanitarian mission, which was pronounced and, in fact, was successful fairly quickly. After that, I don't think many people were aware -- I certainly wasn't -- of how that mission had shifted to support U.N. efforts to create a new government in Mogadishu. No one was ready, including the White House, for the kind of pitched battle that happened on October 3rd and 4th.

A second thing I would say is that 1993 was a certain high watermark for people's impression of the impregnability or the invincibility of the American military. The Persian Gulf War had been accomplished so quickly and with so few casualties that most Americans were convinced that our military was so powerful and so effective that it really couldn't be successfully contested. This is also coming on the heels of the collapse of the Soviet Union, with the recognition of the United States being the sole military power of its size and strength in the world. So, it was a very heady period for people's perception of the United States military.

Number one, no one was expecting the kind of fighting that took place in Mogadishu. Secondly, it came as a double surprise, given that the Somalis were essentially just mobs of armed militia against the vaunted U.S. military. So, the images of dead American soldiers being dragged through the streets [were] a tremendous shock.

I was thinking about Mohamed Farrah Aidid in comparison to Osama Bin Laden. I don't think very many people were paying attention, but bin Laden had been reported on consistently for five, maybe even 10 years before 9/11. Was Aidid a name that people who were paying attention would have known before this attack took place or was he a new character on our radar?

Completely new. He was really only known in Somalia, in Mogadishu, which was a place that was so obscure. I doubt very many Americans could have found it on a map. Certainly Aidid, unlike Bin Laden, had never declared war on the United States of America and had never been linked to any international terrorism. He was a local figure in Somalia, primarily in Mogadishu, who was the head of one of the more powerful of the local clans. Other than people who were working in country, his was not a name that anyone would have recognized.

So, it's the nineties, you're working for a daily newspaper in the U.S. How do you convince your editors to let you devote the time to tell this story?

Well, to begin with, I didn't even try. Usually the way I worked was I would find something that I was interested in and I would get the newspaper to support me as much as I could. In the case of something that might turn out to be a book, I might give the Inquirer a magazine piece or a couple of articles that would see me into the reporting process. Then, at some point, I would need to get a book contract in order to be able to go out and fully write the book.

I had made some efforts to get the Inquirer to support my reporting about this battle without any success, initially. In fact, notably without success. Nobody thought this was important or worth doing. I started, actually, reporting the story on my own dime, which basically I just charged my travel and expenses to my credit card. I figured that I would eventually be able to get somebody at the Inquirer to pay it. And I did, ultimately, but they weren't all that interested.

What happened was I got a job offer from The New York Times, and the editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer was eager for me to stay, so he matched the offer from The New York Times and added that I could do anything I wanted. At that point, I told him, "Well, here's what I really want to do, but it's a book." And he said, "Why don't you do it, and we'll run it as a serial in the newspaper before it's published as a book?" And that was how that came to be.

RELATED: Eric Bana Shares Memories of Making the Classic War Movie 'Black Hawk Down'

What was the response to your articles and the book? At what point did you get a movie deal?

The series started, if I remember correctly, in late November or December of 1997, and it was an immediate hit. At the time, the Inquirer's web presence was very small, but the greatest number of hits that they had ever gotten at their website was like 9,000 in a day and that was the day that Philadelphia Phillies second baseman Richie Ashburn died. And this story began getting 10, 20, 30 -- 40,000 hits a day, from all over the world, so there was tremendous excitement over it.

The newspaper circulation went up while the series was running. I remember the head of circulation came into the newsroom and asked to be introduced to me. That's the first time that ever happened.

Right around that time, Jerry Bruckheimer bought the movie rights.

So, that's before the book came out?

Yes, but I think it was after I had finally gotten a publisher for the book. My intention with "Black Hawk Down" all along was to write a book and I had struck out, not just at the Inquirer, but with every major publisher in New York. They all turned down my proposal for "Black Hawk Down." I ultimately made a deal with Morgan Entrekin at Grove/Atlantic, who didn't have a lot of money to give me as an advance, but he liked the idea and thought it would make a good book.

So at that point, I was just delighted to have a publisher. I had been enabled to report the story by the Philadelphia Inquirer, but I had also made a deal with the editor that I would own the rights after initial publication, which is what gave me the opportunity to sell it to a publisher. That's where things stood when the series started in the paper, and then Jerry Bruckheimer bought the movie rights.

Did you have any involvement with the movie? Did you see the script as it was being written or did you have a chance to visit the set?

Chad Oman had come across the series in the newspaper. I don't know whether my agent tipped him off to it or he came across it on his own, but Jerry bought the movie rights off of the serial in the newspaper. He invited me to come out to meet him in Santa Monica. As part of the deal, I had given myself the opportunity to do the first draft of the screenplay, and I had never written a screenplay before.

I remember flying out to Santa Monica and meeting Jerry, and he told me how excited he was to have the project and that he really wanted to make a movie different than any of his other movies -- his other films being things like "Top Gun." And, at that point, I think he had made "Armageddon." They were kind of pop, almost fun, but sort of comic book movies, and Jerry said he wanted to make a very realistic, almost documentary-like version of this story and wanted it to adhere very closely to what I had written.

I remember thinking at the time, "Oh, this was probably what they always tell the writer when he shows up." But Jerry was absolutely true to his word. From the beginning, he was determined to make "Black Hawk Down" as realistically and as faithfully as possible, and I think he did that.

As far as my involvement, I did the first draft of the screenplay. It was the first screenplay I had ever written, and then they subsequently hired Ken Nolan, who is a much better screenwriter than I am. He, as far as I know, paid very little attention to my first draft in crafting his own take on it.

Then Ridley Scott came onboard to direct, and Ridley went back and read my original account. There were certain things in my screenplay that he really liked, mostly having to do with creating roles for Somali characters, so some of those ideas in my draft got incorporated into Ken's work on the screenplay. But, in the end, I felt that the screenplay was Ken Nolan's work.

It's been over 25 years since the battle in Mogadishu and it's 15+ years since the movie. How much has it stayed a part of your life over time?

It's huge. It was a life-changing experience for me. The book itself was, and then the film just made it that much more so. After "Black Hawk Down" came out as a book, which was before the film, it was a #1 best seller on The New York Times list, it was a National Book Award finalist, it got a lot of attention, and it sold really well.

And yet I would still run into people all the time who would, after I'd been introduced to them, they would ask, "What do you do for a living?" and I'd say, "Oh, I'm a writer." And they'd say, "Oh, really, what have you written?" And I would say, my last book was called 'Black Hawk Down.'" And they would say, "Really, what was that about?" After the movie came out, no one in my life has ever asked me that question again. Anywhere in the world, people know what "Black Hawk Down" is.

It's led to tremendous opportunities for me as a journalist, and it's been very rewarding financially. It was a terrific, terrific experience for me.

When we interviewed you about your book "Hue 1968," you hinted that there was possibly a deal with Michael Mann for a series. Can you give us an update on the status there?

I did make a deal with Michael. He has made his own deal with FX. He is well along preparing to shoot this as an eight- to nine-hour-long miniseries on location. He was unable to get permission to shoot in Vietnam but, as of right now, he's building sets in [the Philippines] and Thailand. He was still waiting for a greenlight from FX, but it's a very expensive project, so it's not surprising that they're being careful about it.

But he's got scripts for almost all of the episodes, which I think are amazing, and I've been giving him feedback about those scripts. I met with him 10 days ago, I guess a week before last, when I was in LA, and they were showing me pictures of the work that they've done and the construction that's taking place, so it appears to me as though it's on the verge of happening.

I guess we all need to call Disney since it's their dime now that they own FX.

Yes, exactly. I think that's actually what's held up some of the authorization to go ahead because it's just such a big-ticket item. I think nobody wanted to sign off on it while this deal with Disney was still being worked out.

Let's talk about your true crime story, "The Last Stone." What was the backstory there?

This is the first big story that I ever covered as a reporter. I was 23 years old at the Baltimore News-American when these two sisters disappeared. I spent weeks covering the story, getting to know the family and the detectives who were working on it. And, of course, there was never any resolution to it. The fact that these two little girls had vanished and no one knew why or who had done it for all these years always haunted me, as it would anyone who had gotten close to the story.

In 2015, I read a little article in The Washington Post that said that they had zeroed in on a suspect in the Lyon sisters' case. I drove down to Maryland, and I interviewed the detectives who worked on it. They explained how they had built their case against Lloyd Welch. I thought this is something I want to do. I want to write an ending to that story.

This book could make a great movie. Almost the entire picture could take place in that police interview room. There are so many amazing characters.

It's a great role for somebody as Lloyd. I think that right now there are a couple different studios that are interested in it. We haven't made a deal, but I think we probably will sell the movie rights here soon. Of course, many people sell the movie rights to things, but nothing gets made, so we'll have to wait and see if anything comes of that.

The book was a real challenge. When I started working as a reporter, if I was writing a story and there happened to be some audio or some video or a still photograph, that was a very rare thing and I always tried to make the most of it.

Nowadays, given the fact that cameras and recorders are almost everywhere, omnipresent, it's actually remarkable that more and more, when I write a true story, I have the actual raw material, the recordings.

With "Black Hawk Down," for instance, I had recordings or transcripts of all of the radio traffic during the battle. That's increasingly becoming a challenge for nonfiction writers. I ended up watching 70+ hours of video of Lloyd Welch being interrogated. What's in the book, even though there's a lot of it in there, represents only about 1/100th of everything that I watched. Editing that down was a big challenge in writing that book.

Part of what's great is how repetitive Lloyd is in the book and how irritating that is. I can only imagine how much of it you had to wade through with all of the hours. Your brain must have melted.

I remember my wife asking me, "When are you gonna finish this thing? I'm so sick of hearing this guy's voice." Because I'd be watching it on my laptop, and she'd be having to hear it.