Richard Rice served nearly 30 years in the U.S. Army Special Forces, participating in every major conflict and mission of his generation. He is a senior adviser at GORUCK.

I'm proud of my 30-year Army career with various Special Forces units, starting with the 5th Special Forces Group. That service began with the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam -- Studies and Observation Group (MACV-SOG). Throughout my career in special operations, it was my honor to serve with some of the finest and bravest soldiers I've ever seen.

For many years, I listened to my friends and the people I served with talk about their trips back to Vietnam. It was interesting to hear, but I was never prepared to spend the time or effort to do so myself. More importantly, I wasn't sure if I really wanted to go back and remember those years.

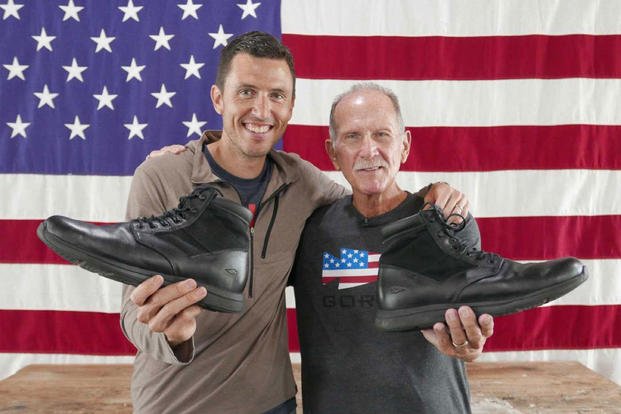

What took me back to Vietnam more than 45 years after I last left wasn't a journey of discovery, but a business trip with GORUCK, a veteran-owned company that builds gear and leads hundreds of events each year to develop and promote rucking as a fitness activity. Yet this was no normal business trip.

The journey to Vietnam was driven by a mission to build and test the MACV-1, a boot that would meet today's Special Forces standards but remain true to the heritage of the jungle boots that carried me and many other Special Forces soldiers through a multitude of adventures around the world.

The basic reason for the trip was to visit the factory where the boots would be made and test them along the way. But when GORUCK CEO Jason McCarthy, a former Army Green Beret, opened the door to go "wherever else I wanted to go," I knew I had the opportunity to find something more. So, we made our way across the country, testing the boots and searching for that something more, taking me to locations that both haunted and healed me a generation after they were a battlefield.

I returned to places like Long Thanh, where I heard my first shots of the war; the Caravelle Hotel in Saigon, which had a gorgeous rooftop bar where we watched mortar attacks on the outskirts of the city while enjoying drinks; my base camp at Ban Me Thuot in the Central Highlands; and Dalat, a cultured city with beautiful French architecture.

This last visit was particularly chilling. The clouds that envelop the mountains and provided coverage for the enemy during the war still spook me decades later. Even though I knew the war was far in my past, my body and instincts reacted viscerally to the memories, leaving my head on a swivel and my eyes constantly searching for threats that no longer exist in a country that is no longer a threat.

Intellectually, I understood that the jungles and hills of Vietnam held no threats, but my emotional side equally felt the need to be aware. But I had always thought and still think that the jungle is a beautiful place. It's a great thing to see and enjoy, even though it is a terrible place to fight a war. Gradually, I found myself able to stop and breathe -- to enjoy the beauty and to live in the current moment.

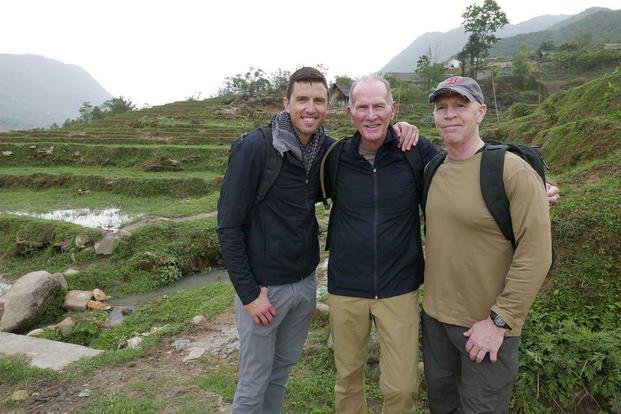

As we tested prototypes of the boots over several years, we accessed many locations I had hoped to visit under different circumstances. Part of the field testing included a trip to Sapa in the north of Vietnam near the Chinese border. After that test was complete, we returned to Hanoi, a beautiful city that reminded me of the Vietnam I remembered. As we walked around in the evening, we found ourselves standing outside the Hanoi Hilton, where American prisoners of war had been held. Many levels of emotion coursed over me and my teammates, but mainly frustration, since so much study had gone into identifying possible POW rescue opportunities during the war, though none proved feasible.

For the current generation of veterans -- especially those who spent extensive time in Afghanistan and Iraq -- the wars they fought in are not yet a closed chapter in world history. It's too early for them to know what their legacies are and what their battlefields will become when the U.S. leaves the stage. But they are already grappling with these same questions, while also trying to forget experiences that scarred and otherwise affected them. Some will seek closure as soon as possible, while others who are more like me may wait many decades and return for ostensibly different reasons in the far future.

Unpacking war takes time, and sometimes we simply aren't interested in doing so. While I wasn't sure what to expect from my own return to Vietnam, what developed was surprising. It helped me honor those who had fallen, closed a loop for me that had been open for years, and gave me peace.

-- The opinions expressed in this op-ed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Military.com. If you would like to submit your own commentary, please send your article to opinions@military.com for consideration.