(In the coming months, Military.com will profile companies that have provided significant support to the U.S. military in times of national crisis. This is Part I of a three-part series profiling General Motors' contribution to America's warfighting capabilities during World War II.)

America wasn't at war as Adolf Hitler's military blitzkrieg’d its way across Poland in September 1939, but the lessons that emerged from that swift German victory weren't lost on thought leaders -- both in government and industry -- in the United States.

More than anything else, the internal combustion engine played the leading role in Nazi Germany's new type of warfare. The motorized Panzer Divisions, composed of tanks and self-propelled artillery, thundered into Poland. Waves of Stuka dive bombers terrorized civilians behind the Polish lines and destroyed communications to the rear. It was over in a matter of days.

As Poland fell and Britain and France declared war on Germany, the U.S. government reached out to industrialists to discuss proposed military requirements in the event the nation was dragged into the war. Among those companies that government reps approached was one that would ultimately provide the lion's share of hardware to the American military: General Motors.

Two main factors made GM well-suited to answer the nation's needs during the march to war: Corporate leadership had the right attitude about what had to be done, and the company divisions were structured with enough autonomy to allow them to tackle vastly different military production requirements moving forward.

The right corporate leadership attitude started at the very top of GM. About the time the Nazis advanced into Holland, Belgium and France in the late spring of 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked GM chief William S. Knudsen to head the new National Defense Advisory Commission.

"Big Bill" felt like he had no choice but to accept the offer. As he told his daughter when she asked why he was making such a professionally risky move, Knudsen said, "This country has been good to me, and I want to pay it back." Knudsen relocated to Washington to lead the mobilization of American industry to build the nation's defense arsenal (a move that ultimately came with significant personal cost).

Meanwhile, back in Detroit, new GM president C.E. Wilson began shepherding the corporation into its "guns and butter" phase -- the period where GM made its first moves toward manufacturing military hardware while maintaining a steady level of civilian-focused automobile production. Wilson challenged each GM division with basic military projects, ones that, where possible, fit with that division's commercial expertise and production facilities.

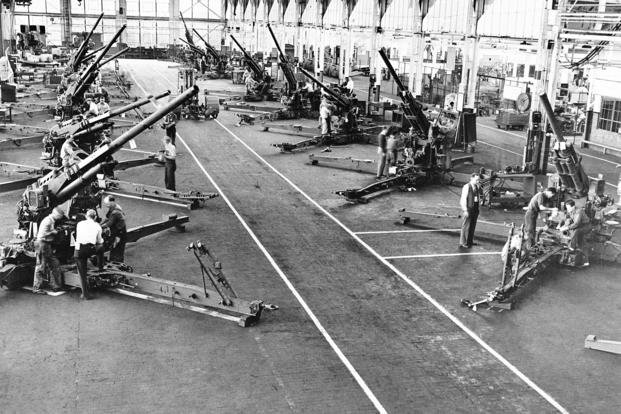

These early efforts were done under the U.S. government's "Lend-Lease" program designed to assist the allies in the European Theater. In short order, GM was tackling the manufacture of machine guns, rifles and Navy guns to arm ships ferrying war supplies across the Atlantic. One of the first contracts with the French covered an order for 700 V-1710 Allison aircraft engines.

That delivery was never made, though, because there was no agency on the French side to assume custody (or make payment) as the government crumbled in June -- tangible evidence to an otherwise detached American workforce that the situation for our friends in Europe was rapidly deteriorating.

Although GM might have been organizationally postured to answer the military's needs better than most large American companies at the time, that still didn't make the undertaking easy or immediate. In essence, GM was being asked by the United States government to start a new business.

As the requirements came in, it became obvious that GM's manpower was generally deficient in its understanding of what it was going to take to bridge the difference between material "on order" and material "on hand." Materials for defense were more highly stressed and had to be made with a greater degree of accuracy; which was to say, they were not designed with mass production in mind, at least not the auto industry's approach to mass production.

A good example of this was the difference between the manufacture of a car engine and a military aircraft engine, something Allen Orth described in his internal corporate document titled "The War Years" written in 1956.

In the paper, Orth outlines that the Cadillac automobile engine, which was one of the finest in the automotive field, had been developed for nearly 30 years by an organization facing continuous marketplace competition to develop max value per dollar of cost. The result was an engine weighing about six pounds per horsepower.

On the other hand, airplane engines were designed around getting the greatest horsepower in a structure of the lowest possible weight and bulk, and that design yielded an engine that weighed only about one pound per horsepower.

So as the Cadillac motor manufacturing line undertook the building of Allison-designed military airplane engines, the team faced a steep learning curve, to put it mildly. Orth used the differences in connecting rods as an example.

The Cadillac engine required 25 matching operations while that for the Allison airplane engine required 93 operations -- almost four times as many. There were two-tenths of a man-hour of labor on the Cadillac rod compared to 11 man-hours -- 55 times more -- on the Allison. And the Allison engine required not only more workers but more and radically different machine tools.

The 10 months of GM's "guns and butter" period ended abruptly with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The nation forgot about peacetime products and clamored for war supplies. What had been defense production became war production.

And in early 1942, GM completely dropped its commercial automobile business and turned entirely to the manufacture of military trucks, planes, engines, weapons and ammunition. At the same time, 114,000 of the company's employees left to fight the war.

As GM went "all-in" behind defeating the Axis Powers, Lt. Gen. Brehon Somervell, the U.S. Army supply chief at the time, toured a few of the Michigan factories. At the tail end of his visit he said, "When Hitler put his war on wheels, he ran it straight down our alley. When he hitched his chariot to an internal combustion engine, he opened up a new battlefront -- a front we know well. It is called Detroit."

For more on GM and its contributions to the U.S. military throughout history, visit the GM Military History page.

Find the Right Veteran Job

Whether you want to polish your resume, find veteran job fairs in your area or connect with employers looking to hire veterans, Military.com can help. Subscribe to Military.com to have job postings, guides and advice, and more delivered directly to your inbox.