In July 1917, the all-Black 3rd Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment, traveled by train from Columbus, New Mexico -- near the Mexican border -- to Houston. They were tasked with guarding the construction of an auxiliary National Guard training facility.

The soldiers could not have fully imagined what awaited them.

Their assignment to guard Camp Logan was scheduled to last seven weeks. It barely lasted a month, cut short by a race riot that resulted in 20 deaths and three courts-martial. Nineteen soldiers were executed, and 63 were given life sentences.

Those verdicts stemming from the Houston Race Riot of 1917 might not be final, though. As of June 2022, the Army is reviewing a clemency petition for all 110 soldiers convicted after the three military proceedings resulting from the riot, a spokesman for the service confirmed to Military.com.

"The denial of justice can never fully be undone," Michael F. Barry, the president and dean of the South Texas College of Law Houston, told The Associated Press.

After the United States entered World War I, it announced the establishment of Army training camps to prepare troops to be deployed to Europe. One was Camp Logan, located west of downtown Houston.

"The caveat, for Houstonians, was that the installation came free of black soldiers, a common request for cities, especially in the South, that sought military business," according to research from Prairie View A&M University.

It was in this climate of racial discrimination and hostility that the 24th Infantry Regiment -- including more than 650 Black soldiers and their white commanding officers -- was dispatched. Houston leaders vowed there would be no racial trouble, a claim that soon proved hollow.

Entrenched in the era of Jim Crow, police officers harassed and abused Black soldiers. When service members received passes to go into the city, they endured slurs and acts that made clear that their military uniform did not shield them from discrimination, as they thought it might. Their sheer presence was viewed "as a threat to racial harmony."

Tensions intensified on Aug. 23, 1917, after police pistol-whipped and arrested a private from the 24th for intervening in the arrest of a Black woman. When Cpl. Charles Baltimore, a military policeman with the battalion, inquired about the private's condition, he was shot at, chased into a nearby home and taken to the police station.

The Houston Race Riot of 1917 involved soldiers from the all-Black 3rd Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment and resulted in the execution of 19 of them.

Although Baltimore was released, a rumor reached the regiment that he had been killed. Reports of a white mob heading to the camp added to the confusion, leading more than 150 soldiers to defy orders to stay on base. They grabbed rifles and "began firing wildly in the direction of the supposed mob," an account from the Texas State Historical Association said.

According to the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative's version of the incident: "Seemingly under attack by local white authorities, over 150 Black soldiers armed themselves and left for Houston to confront the police about the persistent violence. They planned to stage a peaceful march to the police station as a demonstration against their mistreatment by police. However, just outside the city, the soldiers encountered a mob of armed white men."

Sixteen white civilians, including five police officers, died, as well as four Black soldiers.

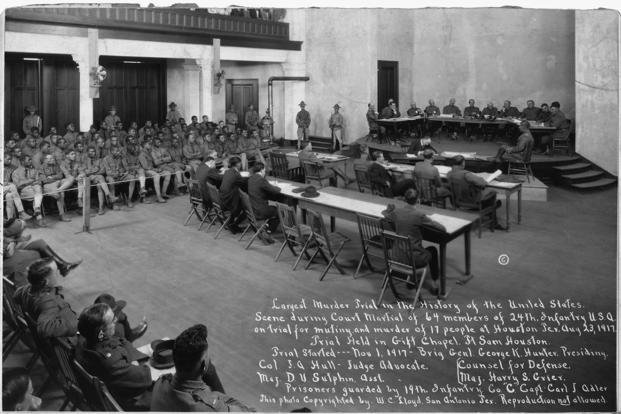

Soldiers faced a variety of charges, including disobeying lawful orders, mutiny, assault with intent to commit murder, and murder. At the first court-martial, barely more than two months after the riot, more than 60 soldiers were tried in the largest murder trial in U.S. history.

"A single attorney working on a mere two weeks preparation" represented every defendant. Thirteen of them, including Baltimore, were sentenced to death and not allowed to appeal. They were informed of their sentences on Dec. 9 and hanged two days later.

"I am to be executed this morning," Baltimore wrote to his brother. "... It is true I went downtown with the men that marched out of camp. But I am innocent of shedding any blood. But it is God's will, so don't worry. ... Meet me in heaven."

The outcry about the soldiers' treatment led the Army to change its appellate review process. Sixteen more soldiers received death sentences at the next two courts-martial, but President Woodrow Wilson commuted 10 of those to life terms.

Some soldiers served up to 20 years in prison before their release, according to Prairie View A&M. Two white officers were court-martialed but released; no white civilians faced charges.

-- Stephen Ruiz can be reached at Stephen.Ruiz@military.com.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.