When Soviet-backed North Korean forces invaded South Korea in June 1950, American military planners anticipated the worst. They saw the conflict as the potential start of World War III. While the Korean War escalated, strategists worried an enemy invasion could come through Alaska's frozen wilderness, just a few miles from Soviet territory across the Bering Strait.

To combat the potential Soviet invasion were 89 ordinary Alaskans willing to become something extraordinary.

From 1951 to 1959, the FBI and Air Force ran Operation Washtub, a covert program that trained bush pilots, trappers, hunters and miners to operate as covert agents if Soviet paratroopers ever landed in Anchorage or Fairbanks. The program remained classified for more than 50 years until documents were declassified in 2014, uncovering one of the Cold War's most unusual operations.

How the FBI Built a Secret Spy Network in America's Last Frontier

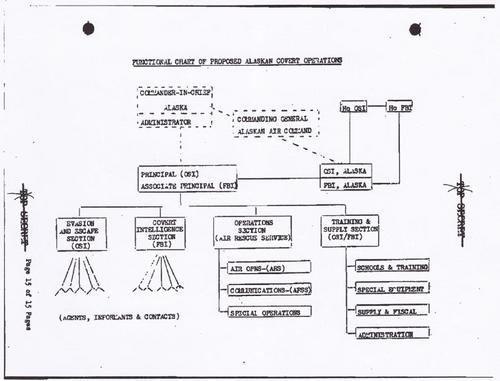

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover partnered with Joseph Carroll, his former protégé who led the newly created Air Force Office of Special Investigations, to launch Operation Washtub in early 1951. According to the declassified documents, the plan was to build an intelligence network of civilians who could gather information and report enemy movements if Alaska ever fell to Soviet occupation.

The agents needed to blend in. Military intelligence officers or government employees would be obvious targets for Soviet troops trained to eliminate local resistance. Instead, recruiters looked for permanent Alaskan residents with established livelihoods and legitimate reasons to be in remote locations.

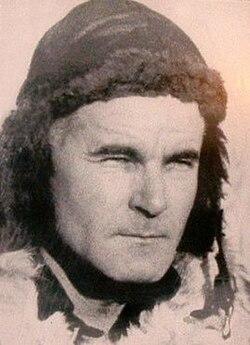

Bush pilots fit perfectly. They already flew to isolated mining camps and villages, making their movements less suspicious. Meanwhile, their bird’s-eye view could document and report on Soviet positions. Legendary aviator Bob Reeve, founder of Reeve Aleutian Airways and known as “the glacier pilot,” was among those background checked by the FBI, though he never publicly confirmed that he was recruited.

“Bob Reeve pioneered glacier flying and proved the airplane offered the key to the future of Alaska,” said Jimmy Doolittle, the famous World War II commander. Reeve had already proven his skills flying military supplies throughout the Aleutian Islands during WWII, earning him the distinction of being one of the only civilian pilots authorized to fly in combat zones.

Training took place in Washington, D.C., where Alaskan agents learned espionage basics: coding and decoding messages, covert photography, map reading, close combat, and arctic survival techniques. The FBI trained each agent separately to prevent compromise if one was captured. The training also covered Russian uniforms and equipment so agents could recognize enemy forces.

Military Survival Caches Hidden Across Alaska's Wilderness

The program scattered survival caches across Alaska's frozen landscape, hidden in caves, remote cabins, buried underground, or tucked into distant forests. Each cache cost about $2,500 to prepare and stock in 1951, equivalent to roughly $29,000 today, according to the Anchorage Daily News.

Inside these hidden stockpiles were tools for both survival and espionage. Agents would find .30-06 semiautomatic rifles with telescopic sights, small-caliber pistols fitted with silencers, 150 feet of climbing rope, commercial skis, snowshoes, radio equipment, explosives to destroy evidence, and $500 in gold or silver coins for bartering. The supplies included everything needed to survive Alaska's brutal winters while gathering intelligence on enemy positions.

Agents received $3,000 annually to remain on standby, with the promise of doubled pay if a Soviet invasion became reality. The average age of the recruits was 50 years old.

Other than Reeve, the documents identified several agents including Dyton Abb Gillard, Guy Raymond, a heavy-set tin miner from Lost River who had tattoos of a dagger and an eagle on his arms, and Ira Weisner from the gold mining town of Rampart.

One FBI profile described an ideal candidate as a professional photographer in Anchorage with only one arm, reasoning he wouldn't benefit the enemy in any labor battalion. The document noted he was “reasonably intelligent, particularly crafty, and possessed of sufficient physical courage as is indicated by his offer to guide a party which was to have hunted Kodiak bear armed only with bow and arrow.”

These ordinary Alaskans led relatively normal lives in the last frontier, though their experience flying, hunting, navigating the harsh terrain and their courage was exactly what the government wanted for the mission.

However, the program deliberately excluded Alaska Native populations. Declassified FBI documents reveal racist reasoning, claiming “the selection of agents from the Eskimo, Indian, and Aleut groups in the Territory should be avoided in view of their propensities to drink to excess and their fundamental indifference to constituted governments and political philosophies.”

Why Operation Washtub Failed Before It Ever Began

Hoover pulled the FBI from Operation Washtub in September 1951, less than a year after it started. In the margins of one memo, he scribbled his concerns about another intelligence failure: “If a crisis arose we would be in the midst of another 'Pearl Harbor' and get part of the blame.” He ordered his agents to “get out at once.”

The Air Force continued the program alone until 1959, when Alaska gained statehood. By then, the costs of maintaining 89 agents and weatherproofing caches against Alaska's extreme temperatures had become unsustainable. Meanwhile, the end of the Korean War and Stalin's death brought a temporary lull to Cold War.

Outside Online noted that an account published in a military history journal in 1988 claimed many of the caches were already looted by hunters and trappers. An Army Corps of Engineers search in 1989 came up empty-handed, though some of the caches may still be hidden somewhere across America's largest state.

Deborah Kidwell, official historian of the Air Force Office of Special Investigations, later wrote in the agency's magazine that the survival caches ultimately served a vital peacetime purpose for decades after the operation was called off. Many of the stashes were maintained as emergency supply stations for survivors from aircraft accidents.

Bob Reeve never publicly confirmed his role in Operation Washtub. But when his biographer Beth Day asked if Alaskans feared the Russians crossing the Bering Strait, Reeve gave an answer that hinted at his confidence in the program's agents.

“Hell no,” he said. “If we don't knock 'em down like pigeons before they get across the Alaskan Range, we Alaskans, each with a half-dozen guns and ammunition, will just kick their teeth out.”

The Soviet invasion never came. Operation Washtub ended without a single agent ever activating their hidden cache or sending a coded message about enemy movements. But for eight years, ordinary Alaskans carried that secret, ready to stay behind while others fled if the Cold War ever turned hot in America's frozen north.